NYT crossword clues, renowned for their wit and complexity, offer a fascinating window into the art of puzzle construction. This guide delves into the structure, style, and evolution of these clues, exploring the techniques employed by constructors to create both challenging and rewarding experiences for solvers of all levels. We’ll examine the different types of clues, from straightforward definitions to intricate wordplay, and analyze how context, themes, and word selection contribute to their overall difficulty and impact.

From understanding the grammatical nuances of clue construction to mastering the art of misdirection, this exploration will equip you with the knowledge and insights to appreciate—and even craft—your own NYT-worthy crossword clues. We’ll investigate the historical evolution of clue styles, showcasing how techniques have adapted and evolved over time, and provide a practical framework for constructing effective and engaging clues.

Prepare to unlock the secrets behind the seemingly simple, yet remarkably intricate, world of the New York Times crossword puzzle.

Crossword Clue Structure and Style

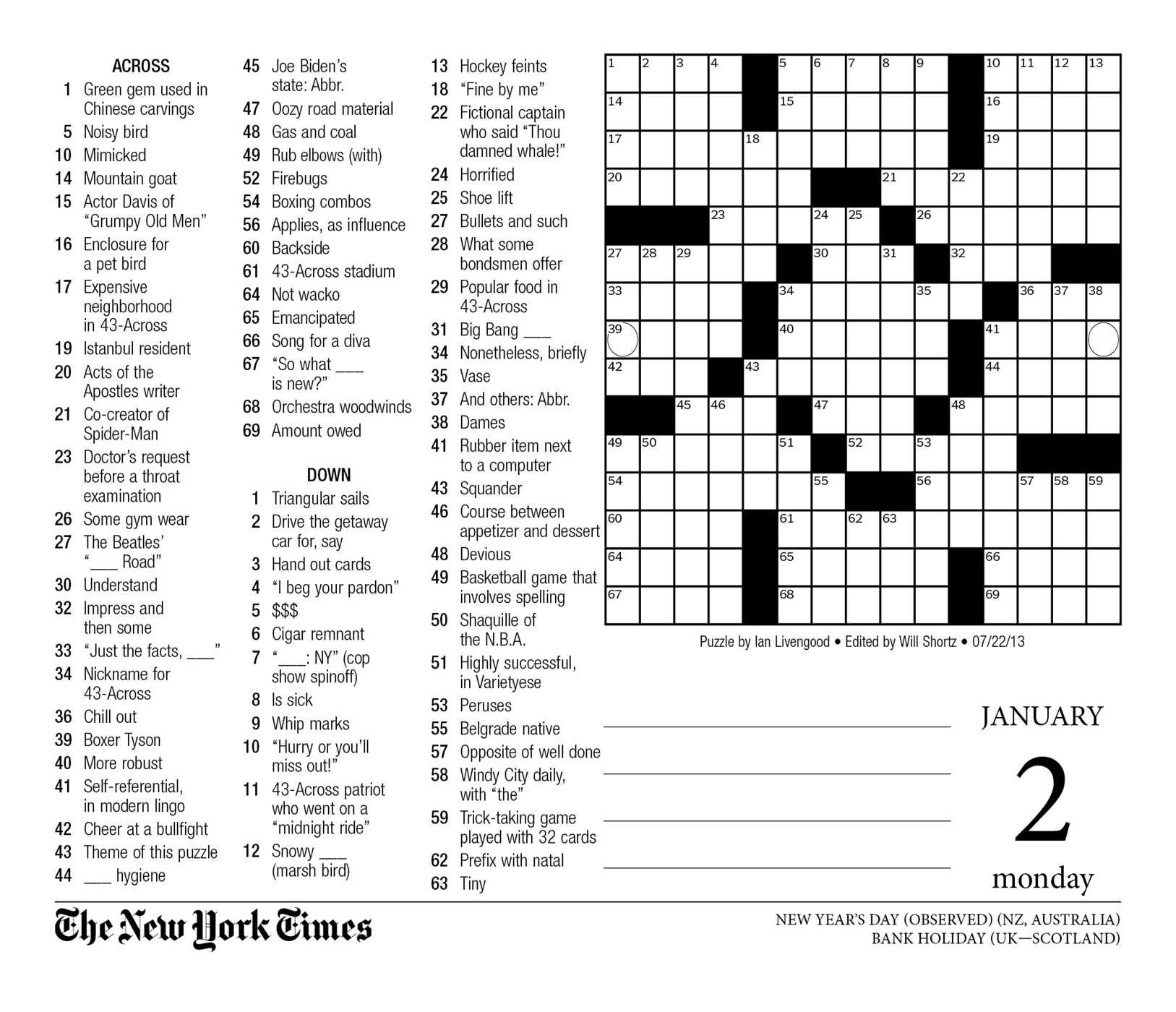

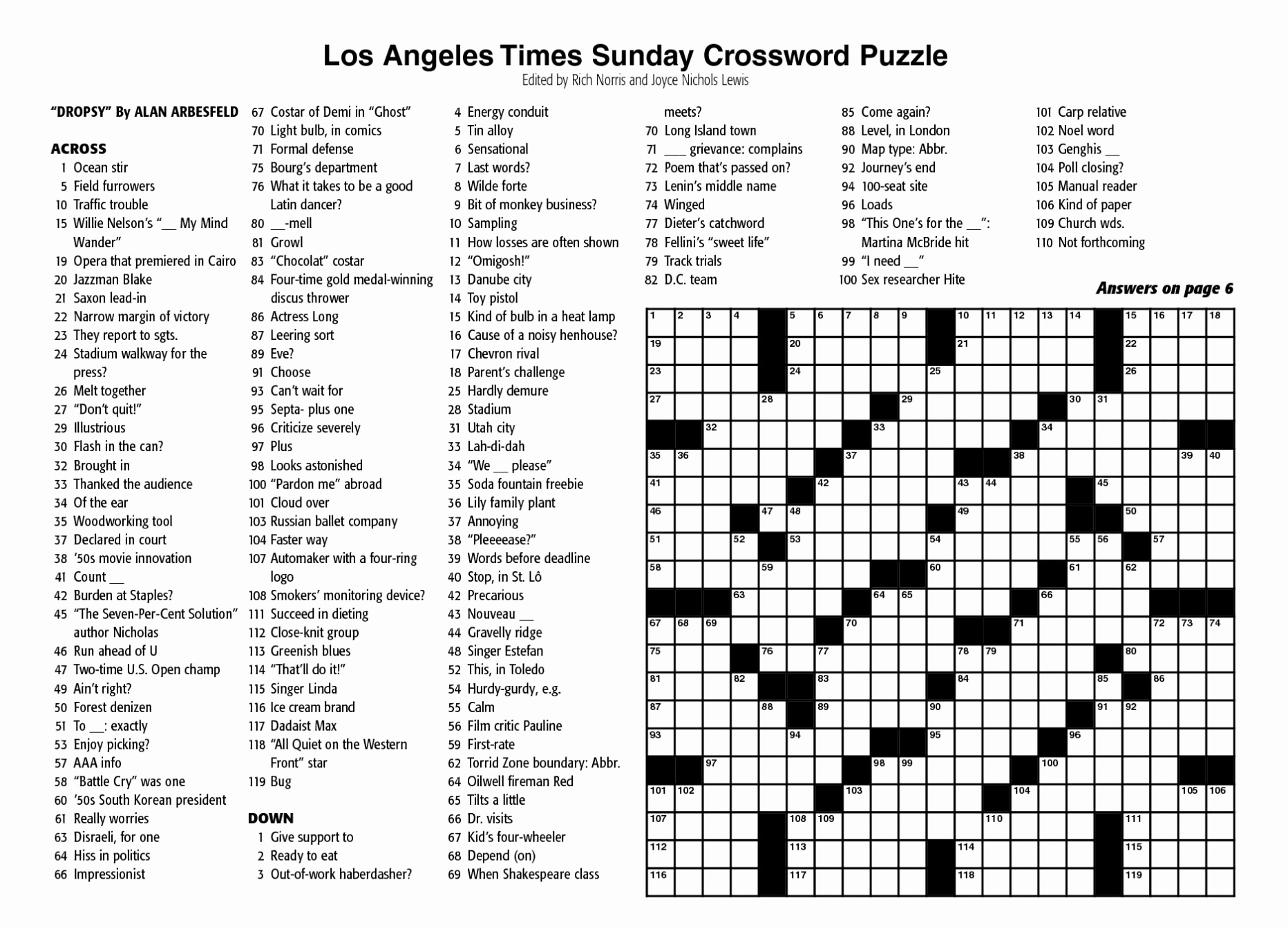

The New York Times crossword puzzle is renowned for its challenging and cleverly crafted clues. Understanding the structure and style of these clues is key to successfully solving them. The clues often employ a combination of straightforward definitions and wordplay, requiring solvers to think laterally and creatively.

The grammatical structure of NYT crossword clues varies widely, depending on the clue type. Straightforward clues typically present a direct definition of the answer. Cryptic clues, however, utilize wordplay, often incorporating puns, anagrams, hidden words, or reversals, along with a definition or a misleading element. The overall structure aims for brevity and precision, packing a significant amount of information into a concise phrase.

Common Clue Types, Nyt crossword clues

The NYT crossword puzzle utilizes a variety of clue types to create engaging puzzles. These clue types often overlap and blend together, requiring solvers to recognize the different techniques employed.

Straightforward clues offer a direct definition or synonym of the answer. Cryptic clues incorporate wordplay, requiring solvers to decipher the wordplay to arrive at the answer. Puns use words with similar sounds but different meanings to create a humorous effect and lead to the answer. Other techniques include anagrams (rearranging letters), hidden words (words contained within other words), and reversals (words spelled backward).

Examples of Clues Using Different Wordplay Techniques

Here are some examples illustrating various wordplay techniques:

- Anagram: “Upset dog (5)”

-Answer: GODLY (letters of “dog” rearranged) - Hidden Word: “Part of a painting found in ‘masterpiece’ (6)”

-Answer: PIECE (hidden within “masterpiece”) - Reversal: “Turned around, went back (4)”

-Answer: EWON (reversed “NOWE”) - Pun: “Sound of a sheep? (3)”

-Answer: BAA (sounds like “baa” the sheep sound)

Misdirection and Wordplay in NYT Clues

A hallmark of NYT crossword clues is the use of misdirection and wordplay. Misdirection leads the solver down a seemingly logical path that is ultimately incorrect, forcing them to reconsider their initial assumptions. Wordplay often involves puns, double meanings, or cryptic references. The combination of these techniques creates a challenging and rewarding experience for the solver. For example, a clue might use a common phrase in an unexpected way, or employ a word with multiple meanings to create a deceptive clue.

NYT crossword clues can be surprisingly challenging, requiring a broad range of knowledge. For instance, understanding the recent business news, such as the complexities surrounding mosaic brands voluntary administration , could provide an unexpected advantage in solving a clue. This highlights how seemingly unrelated events can find their way into the cryptic world of NYT crossword puzzles, making them even more engaging.

The solver must recognize the wordplay and overcome the misdirection to find the correct answer.

Comparison of Straightforward and Cryptic Clues

| Clue Type | Structure | Wordplay | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Straightforward | Direct definition or synonym | None | Big cat (5)

Answer LION |

| Cryptic | Combination of definition and wordplay | Anagrams, puns, hidden words, reversals, etc. | Slightly mad, running around the country (7)

Answer UNHINGED (anagram of “running” around “HE” for country) |

Difficulty and Word Selection

The New York Times crossword puzzle boasts a wide range of difficulty, appealing to both novice solvers and seasoned experts. The difficulty isn’t solely determined by the number of obscure words, but rather a complex interplay of word selection, clue construction, and the overall thematic coherence of the puzzle.

Understanding this interplay is key to appreciating the craft of NYT crossword creation.Word selection significantly impacts clue difficulty. The choice of words, both common and uncommon, directly influences the solver’s experience. Common words allow for straightforward clues, providing a foothold for beginners and a sense of accomplishment. Conversely, less common words, or words with multiple meanings, necessitate more intricate and challenging clues, elevating the puzzle’s difficulty.

Criteria for Word Selection

The selection of words for a NYT crossword puzzle adheres to specific criteria. Words must be acceptable in terms of language and usage, generally adhering to standard English dictionaries. Furthermore, the words must fit seamlessly within the grid, considering letter frequency and the availability of crossing words. The ideal word possesses multiple potential meanings or associations, enabling the construction of clever and multifaceted clues.

The overall goal is to create a balanced puzzle with a satisfying mix of accessibility and challenge. Length is also a consideration, with shorter words generally preferred for ease of construction and solving.

Examples of Clues Using Obscure or Uncommon Words

Consider the word “zeugma.” A clue might be: “Figure of speech using one verb to govern multiple words.” This requires a specific knowledge of literary terms. Or, take the word “sesquipedalian.” A possible clue might be: “Characterized by long words.” This clue is self-referential, adding an extra layer of complexity. These examples illustrate how uncommon words demand more sophisticated and nuanced clues, raising the puzzle’s difficulty.

Clue Difficulty and Word Type Categorization

| Difficulty Level | Word Type | Clue Example | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Easy | Common Noun | “Large feline” | Simple definition; answer: LION |

| Medium | Less Common Verb | “To make amends” | Requires slightly more thought; answer: ATON |

| Hard | Obscure Proper Noun | “Author of ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude'” | Requires specific knowledge; answer: GARCIA MARQUEZ |

| Challenging | Archaic Word | “Old-fashioned word for a knave” | Demands familiarity with older language; answer: SCOUNDREL |

The Role of Context and Themes

Context and thematic elements are crucial in understanding and solving New York Times crossword clues. They provide layers of meaning beyond the simple definition, enriching the solving experience and demanding a deeper understanding of wordplay and common cultural references. The interplay between context and theme significantly impacts clue construction and solver interpretation, leading to a more engaging and challenging puzzle.Contextual Clues and Their Influence on InterpretationThe placement of a clue within the crossword grid significantly influences its interpretation.

A clue’s answer might be ambiguous in isolation but becomes clear when considering the intersecting words already solved. The surrounding answers provide valuable contextual information, limiting possibilities and guiding the solver towards the correct solution. For example, a clue might simply be “Capital of France,” which could be PARIS, but if intersecting letters suggest a four-letter answer, the solver might consider other possibilities before arriving at the solution.

Crossword constructors often exploit this interdependence to create elegant and challenging clues.

Context-Dependent Clue Examples

The following examples illustrate how context resolves ambiguity:* Clue: “High-pitched sound” (Assume intersecting letters suggest a three-letter answer). The answer could be many things (e.g., “PEEP,” “YELL,” “SCREECH”), but the context provided by intersecting words might narrow it down to “PEEP” if the letters fit.

Clue

“Part of a ship” (Assume intersecting letters suggest a five-letter answer). This is broad, but the crossing letters could immediately lead to answers like “BOW,” “STERN,” or “KEEL” rather than a more obscure part of the ship.

Thematic Influence on Clue Construction

Recurring themes in NYT crosswords significantly influence clue construction. The theme often dictates the types of answers and wordplay used, creating a cohesive and intellectually stimulating experience. When a theme is present, clues are often designed to subtly hint at the overarching topic, requiring solvers to recognize and utilize this thematic connection.

Common Thematic Elements and Their Impact

Thematic elements in NYT crosswords are varied, reflecting current events, pop culture, and historical references. These themes create a framework within which clues are built, often employing puns, wordplay, and allusions related to the theme.

Examples of Thematic Elements and Clues

Thematic elements often enhance the cryptic nature of clues. A theme can provide a framework for understanding wordplay that would otherwise be obscure.

Below are examples illustrating the impact of thematic elements on clue construction:

| Theme | Clue Example | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Shakespearean Plays | “Scottish play’s villain” | The answer, MACBETH, is directly linked to the Shakespearean theme. |

| American Presidents | “16th president’s nickname” | The answer, HONEST ABE, refers to Abraham Lincoln and is clearly linked to the Presidential theme. |

| World Capitals | “Home of the Eiffel Tower” | The answer, PARIS, is directly related to the world capitals theme, and the clue plays on common knowledge. |

Analyzing Specific Clue Examples: Nyt Crossword Clues

This section delves into the intricacies of New York Times crossword clues by analyzing three examples, highlighting their construction, wordplay, and intended audience. We will examine the techniques employed, comparing and contrasting their effectiveness in misdirection and overall puzzle-solving experience.

Clue Analysis: “Part of a joke” (5 letters)

This clue, for the answer “SETUP,” utilizes a straightforward definition. The word “part” immediately directs the solver towards a component of something larger. The phrase “of a joke” further refines the search, leading to the answer “SETUP,” which is indeed a crucial part of a joke’s structure. The wordplay is minimal; the clue’s strength lies in its precision and clarity.

This clue is suitable for beginners and intermediate solvers due to its lack of cryptic elements or complex wordplay. The effectiveness lies in its directness; there’s little room for misdirection, making it accessible and solvable quickly.

Clue Analysis: “Sound of disapproval” (5 letters)

This clue, for the answer “TSK,” uses a more evocative approach. Instead of a direct definition, it employs a sound-based clue. The phrase “sound of disapproval” immediately evokes the mental image of the sound “tsk,” often used to express mild disapproval. This clue relies on the solver’s auditory association and understanding of non-verbal communication. The misdirection is subtle; one might initially consider longer words related to disapproval.

The effectiveness hinges on the solver’s familiarity with the sound and its cultural context. This clue targets intermediate solvers, requiring a degree of auditory awareness and familiarity with subtle expressions of disapproval.

Clue Analysis: “Where one might find a knight” (4 letters)

This clue, for the answer “CHESS,” is a classic example of misdirection. The phrase “Where one might find a knight” immediately evokes images of medieval settings or perhaps even a heraldic crest. However, the solution lies in the game of chess. The clue’s effectiveness stems from its ability to exploit the solver’s preconceived notions, leading them down a seemingly plausible but ultimately incorrect path.

The wordplay is clever; it plays on the dual meaning of “knight” as both a chess piece and a medieval warrior. This clue is aimed at intermediate to advanced solvers, requiring a broader vocabulary and the ability to think laterally and overcome the misdirection.

NYT crossword clues can be surprisingly challenging, requiring a wide range of knowledge. Sometimes, even understanding the news helps; for instance, recent business headlines might offer clues. Consider the impact of events like the mosaic brands voluntary administration , which could easily inspire a clue related to retail or financial struggles. Returning to the crossword, remember to consider multiple word meanings for a truly satisfying solve.

Comparative Analysis of Clue Structures

The following table compares the structures of the three clues:

| Clue | Type | Wordplay | Misdirection | Target Audience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of a joke (5 letters) | Definition | Minimal | Low | Beginner/Intermediate |

| Sound of disapproval (5 letters) | Sound-based | Moderate | Moderate | Intermediate |

| Where one might find a knight (4 letters) | Double Meaning | High | High | Intermediate/Advanced |

Evolution of NYT Crossword Clues

The New York Times crossword puzzle, a daily staple for millions, has seen a fascinating evolution in its clue style and difficulty over the decades. Early puzzles favored straightforward, often definition-based clues, while modern puzzles embrace a wider range of clue types, including cryptic, pun-based, and misdirection-heavy clues. This evolution reflects not only changes in solver expectations but also the evolving creativity and skill of the puzzle constructors themselves.

The shift in clue construction can be largely attributed to the increasing sophistication of solvers and the desire to continually challenge them. Early clues were primarily straightforward definitions, while modern clues often incorporate wordplay, misdirection, and cultural references, requiring a deeper understanding of language and pop culture.

Clue Styles Across Different Eras

The early 20th-century NYT crosswords, often constructed by Margaret Farrar, featured predominantly straightforward definitions. For example, a clue for “DOG” might simply be “Canine.” As the puzzle’s popularity grew, so did the complexity of the clues. The mid-20th century saw the introduction of more cryptic elements, though still relatively subtle. The late 20th and early 21st centuries witnessed an explosion of creativity, with constructors like Will Shortz championing more challenging and playful clueing styles.

This era saw a significant increase in the use of puns, wordplay, and misdirection, demanding more from solvers. Contemporary puzzles often feature clues that are simultaneously clever and difficult, pushing the boundaries of what’s possible within the constraints of a crossword grid.

Comparison of Clue Styles from Different Constructors

Different constructors have distinct styles, reflecting their individual approaches to wordplay and puzzle design. Some constructors, for example, favor cryptic clues with multiple layers of meaning, while others prefer more straightforward clues with subtle wordplay. Will Shortz, the longtime editor of the NYT crossword, has been instrumental in fostering a diverse range of constructor styles, encouraging innovation and pushing the boundaries of crossword clueing.

A comparison of clues from different constructors reveals a wide spectrum of approaches, reflecting the multifaceted nature of the art of crossword construction. For instance, a constructor known for cryptic clues might offer “Sound of a barking dog” for “WOOF,” while another might use the simpler “Canine’s sound.”

Examples of Clues Exemplifying Specific Eras or Constructors’ Styles

To illustrate the evolution, consider these examples:

- Early 20th Century (Straightforward Definition): “Large feline” for “LION”

- Mid-20th Century (Subtle Wordplay): “Part of a circle” for “ARC”

- Late 20th/Early 21st Century (Cryptic/Misdirection): “What a bee does, briefly” for “HUMS” (referencing the sound of a bee)

- Contemporary (Punning/Cultural Reference): “Like a well-dressed potato” for “SPUDNIK” (a pun combining “spud” and “Sputnik”)

Timeline of Clue Style and Difficulty Evolution

A precise timeline is difficult to establish due to the subjective nature of “difficulty,” but general trends can be observed.

| Era | Clue Style | Difficulty Level | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early 20th Century | Straightforward definitions | Easy | “Bird’s home” for “NEST” |

| Mid-20th Century | Simple wordplay, some cryptic elements | Medium | “Opposite of out” for “IN” |

| Late 20th/Early 21st Century | Cryptic clues, puns, misdirection | Medium-Hard | “Head of state, briefly” for “KING” |

| Contemporary | Complex wordplay, cultural references, sophisticated misdirection | Hard | “What a spy might do with a document” for “DECRYPT” |

Mastering the art of NYT crossword clues requires a keen understanding of language, a flair for wordplay, and a deep appreciation for the subtle nuances of puzzle construction. By analyzing clue structure, word selection, context, and thematic elements, we’ve gained a deeper appreciation for the creativity and skill involved in crafting these challenging yet rewarding puzzles. Whether you’re a seasoned solver or a budding constructor, this exploration has hopefully provided valuable insights into the intricate world of NYT crossword clues, encouraging you to approach these puzzles with a renewed sense of wonder and appreciation.

Query Resolution

What makes a NYT crossword clue “good”?

A good NYT crossword clue is clear, concise, fair, and engaging. It should be solvable with knowledge and deduction, not guesswork, and often incorporates clever wordplay or misdirection.

How are cryptic clues different from straightforward clues?

Straightforward clues offer a direct definition or description of the answer. Cryptic clues incorporate wordplay and often contain multiple parts that need to be pieced together.

Where can I find more examples of NYT crossword clues?

The New York Times website archives past puzzles, and many other online resources offer collections of crossword clues for practice and study.

Are there resources for learning to construct crossword clues?

Yes, several books and websites offer guidance on crossword clue construction, covering techniques, best practices, and examples.